Sartain William Thomas Eakins the Art World 3 No 4 1918 29193

| Thomas Eakins | |

|---|---|

Self portrait (1902) | |

| Born | Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (1844-07-25)July 25, 1844 Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, The states |

| Died | June 25, 1916(1916-06-25) (aged 71) Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, The states |

| Nationality | American |

| Educational activity | Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, École des Beaux-Arts |

| Known for | Painting, sculpture |

| Notable work | Max Schmitt in a Single Scull, 1871 The Gross Clinic, 1875 The Agnew Clinic, 1889 William Rush and His Model, 1908 |

| Movement | Realism |

| Awards | National Academician |

Thomas Cowperthwait Eakins (; July 25, 1844 – June 25, 1916) was an American realist painter, lensman,[1] sculptor, and fine arts educator. He is widely acknowledged to be one of the most important American artists.[2] [three]

For the length of his professional career, from the early 1870s until his health began to fail some 40 years later, Eakins worked exactingly from life, choosing as his subject the people of his hometown of Philadelphia. He painted several hundred portraits, usually of friends, family unit members, or prominent people in the arts, sciences, medicine, and clergy. Taken en masse, the portraits offering an overview of the intellectual life of contemporary Philadelphia; individually, they are incisive depictions of thinking persons.

In addition, Eakins produced a number of big paintings that brought the portrait out of the drawing room and into the offices, streets, parks, rivers, arenas, and surgical amphitheaters of his urban center. These active outdoor venues allowed him to pigment the subject that most inspired him: the nude or lightly clad figure in movement. In the process, he could model the forms of the trunk in full sunlight, and create images of deep space utilizing his studies in perspective. Eakins also took a peachy interest in the new technologies of motion photography, a field in which he is now seen equally an innovator.

No less important in Eakins' life was his work as a teacher. As an instructor he was a highly influential presence in American art. The difficulties which aggress him equally an creative person seeking to paint the portrait and effigy realistically were paralleled and even amplified in his career as an educator, where behavioral and sexual scandals truncated his success and damaged his reputation.

Eakins was a controversial figure whose work received little by fashion of official recognition during his lifetime. Since his expiry, he has been historic by American fine art historians equally "the strongest, near profound realist in nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century American art".[iv]

Life and piece of work [edit]

Youth [edit]

Eakins was born and lived about of his life in Philadelphia. He was the first child of Caroline Cowperthwait Eakins, a woman of English and Dutch descent, and Benjamin Eakins, a writing master and calligraphy teacher of Scots-Irish ancestry.[5] Benjamin Eakins grew up on a farm in Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, the son of a weaver. He was successful in his chosen profession, and moved to Philadelphia in the early 1840s to heighten his family unit. Thomas Eakins observed his father at work and by twelve demonstrated skill in precise line drawing, perspective, and the utilize of a filigree to lay out a careful design, skills he after applied to his art.[vi]

He was an athletic child who enjoyed rowing, ice skating, swimming, wrestling, sailing, and gymnastics—activities he afterwards painted and encouraged in his students. Eakins attended Central High School, the premier public school for practical science and arts in the city, where he excelled in mechanical drawing. Thomas met young man artist and lifelong friend, Charles Lewis Fussell in high schoolhouse and they reunited to report at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts.[7] Thomas began at the academy in 1861 and later attended courses in beefcake and dissection at Jefferson Medical College from 1864 to 65. For a while, he followed his father's profession and was listed in urban center directories as a "writing teacher".[eight] His scientific interest in the man body led him to consider becoming a surgeon.[nine]

Eakins so studied art in Europe from 1866 to 1870, notably in Paris with Jean-Léon Gérôme, being just the 2nd American pupil of the French realist painter, famous every bit a principal of Orientalism.[10] He likewise attended the atelier of Léon Bonnat, a realist painter who emphasized anatomical preciseness, a method adapted by Eakins. While studying at the École des Beaux-Arts, he seems to have taken scant interest in the new Impressionist movement, nor was he impressed by what he perceived equally the classical pretensions of the French Academy. A letter of the alphabet home to his father in 1868 fabricated his aesthetic articulate:

She [the female nude] is the almost beautiful matter there is in the earth except a naked man, but I never yet saw a study of one exhibited... Information technology would exist a godsend to run across a fine human being model painted in the studio with the bare walls, alongside of the smiling smirking goddesses of waxy complexion amidst the succulent arsenic green trees and gentle wax flowers & purling streams running melodious upward & down the hills especially upwards. I hate arrayal.[11]

Already at historic period 24, "nudity and verity were linked with an unusual closeness in his mind."[12] Yet his desire for truthfulness was more than expansive, and the messages domicile to Philadelphia reveal a passion for realism that included, but was non express to, the study of the effigy.[xiii]

A trip to Espana for six months confirmed his admiration for the realism of artists such equally Diego Velázquez and Jusepe de Ribera.[14] In Seville in 1869 he painted Carmelita Requeña, a portrait of a seven-twelvemonth-sometime gypsy dancer more freely and colorfully painted than his Paris studies. That same twelvemonth he attempted his first large oil painting, A Street Scene in Seville, wherein he starting time dealt with the complications of a scene observed exterior the studio.[15] Although he failed to matriculate in a formal caste plan and had showed no works in the European salons, Eakins succeeded in absorbing the techniques and methods of French and Spanish masters, and he began to codify his artistic vision which he demonstrated in his first major painting upon his return to America. "I shall seek to achieve my broad effect from the very get-go",[xvi] he declared.

Early career [edit]

Thomas Eakins House at 1729 Mount Vernon Street, Philadelphia. Benjamin Eakins added the 4th floor in 1874 every bit a studio for his son.

Kathrin Crowell with Kitten (1872)

Eakins' get-go works upon his return from Europe included a large grouping of rowing scenes, 11 oils and watercolors in all, of which the starting time and most famous is Max Schmitt in a Single Scull (1871; also known equally The Champion Single Sculling). Both his subject field and his technique drew attention. His choice of a contemporary sport was "a shock to the artistic conventionalities of the metropolis".[17] Eakins placed himself in the painting, in a scull behind Schmitt, his name inscribed on the boat.

Typically, the piece of work entailed critical observation of the painting's subject, besides as preparatory drawings of the figure and perspective plans of the scull in the water.[eighteen] Its preparation and composition indicates the importance of Eakins' academic training in Paris. It was a completely original formulation, true to Eakins' firsthand feel, and an almost startlingly successful image for the artist, who had struggled with his start outdoor composition less than a year before.[19] His offset known sale was the watercolor The Sculler (1874). Most critics judged the rowing pictures successful and auspicious, but after the initial flourish, Eakins never revisited the field of study of rowing and went on to other sports themes.[20]

At the same time that he made these initial ventures into outdoor themes, Eakins produced a serial of domestic Victorian interiors, often with his male parent, his sisters or friends as the subjects. Abode Scene (1871), Elizabeth at the Piano (1875), The Chess Players (1876), and Elizabeth Crowell and her Dog (1874), each dark in tonality, focus on the unsentimental label of individuals adopting natural attitudes in their homes.[21]

It was in this vein that in 1872 he painted his first large calibration portrait, Kathrin, in which the subject, Kathrin Crowell, is seen in dim light, playing with a kitten. In 1874 Eakins and Crowell became engaged; they were still engaged 5 years later, when Crowell died of meningitis in 1879.[22]

Teaching and forced resignation from Academy [edit]

Thomas Eakins, circa 1882

Thomas Eakins, William Rush Carving His Allegorical Effigy of the Schuylkill River, 1908. Brooklyn Museum

Eakins returned to the Pennsylvania Academy to teach in 1876 as a volunteer later the opening of the school's new Frank Furness designed building. He became a salaried professor in 1878, and rose to managing director in 1882. His teaching methods were controversial: at that place was no cartoon from antiquarian casts, and students received only a short study in charcoal, followed speedily past their introduction to painting, in social club to grasp subjects in true color every bit soon every bit practical. He encouraged students to use photography as an assist to understanding anatomy and the written report of movement, and disallowed prize competitions.[23] Although at that place was no specialized vocational instruction, students with aspirations for using their schoolhouse training for applied arts, such as illustration, lithography, and decoration, were as welcome as students interested in becoming portrait artists.

Most notable was his interest in the instruction of all aspects of the homo effigy, including anatomical study of the human and animal body, and surgical autopsy; there were also rigorous courses in the fundamentals of grade, and studies in perspective which involved mathematics.[24] As an assist to the study of beefcake, plaster casts were made from dissections, duplicates of which were furnished to students. A similar study was fabricated of the beefcake of horses; acknowledging Eakins' expertise, in 1891 his friend, the sculptor William Rudolf O'Donovan, asked him to collaborate on the commission to create bronze equestrian reliefs of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant, for the Soldiers' and Sailors' Arch in One thousand Army Plaza in Brooklyn.[25]

Owing to Eakins' devotion to working from life, the Academy's class of study was by the early 1880s the nigh "liberal and avant-garde in the globe".[26] Eakins believed in teaching by case and letting the students find their ain way with only terse guidance. His students included painters, cartoonists, and illustrators such as Henry Ossawa Tanner, Thomas Pollock Anshutz, Edward Willis Redfield, Colin Campbell Cooper, Alice Barber Stephens, Frederick Judd Waugh, T. S. Sullivant and A. B. Frost.

He stated his teaching philosophy bluntly, "A teacher can do very little for a educatee & should just be thankful if he don't hinder him ... and the greater the master, mostly the less he can say."[27] He believed that women should "assume professional privileges" equally would men.[28] Life classes and autopsy were segregated just women had access to male models (who were nude but wore loincloths).

The line between impartiality and questionable behavior was a thin 1. When a female educatee, Amelia Van Buren, asked about the motility of the pelvis, Eakins invited her to his studio, where he undressed and "gave her the caption as I could not have done by words only".[29] Such incidents, coupled with the ambitions of his younger associates to oust him and accept over the school themselves,[thirty] created tensions between him and the University's board of directors. He was ultimately forced to resign in 1886, for removing the loincloth of a male model in a class where female students were present.

The forced resignation was a major setback for Eakins. His family was split, with his in-laws siding against him in public dispute. He struggled to protect his name against rumors and false charges, had bouts of ill health, and suffered a humiliation which he felt for the residue of his life.[31] [32] A cartoon manual he had written and prepared illustrations for remained unfinished and unpublished during his lifetime.[33] Eakins' popularity among the students was such that a number of them broke with the University and formed the Art Students' League of Philadelphia (1886–1893), where Eakins subsequently instructed. It was there that he met the educatee, Samuel Murray, who would go his protege and lifelong friend. He too lectured and taught at a number of other schools, including the Art Students League of New York, the National Academy of Design, Cooper Union, and the Art Students' Guild in Washington DC. Dismissed in March 1895 by the Drexel Institute in Philadelphia for again using a fully nude male model, he gradually withdrew from education by 1898.

Photography [edit]

Eakins has been credited with having "introduced the camera to the American art studio".[34] During his study abroad, he was exposed to the use of photography by the French realists, though the utilize of photography was still frowned upon equally a shortcut by traditionalists.

In the late 1870s, Eakins was introduced to the photographic motion studies of Eadweard Muybridge, particularly the equine studies, and became interested in using the camera to study sequential motility.[35] In 1883, Muybridge gave a lecture at the Academy, arranged by Eakins and University of Pennsylvania (Penn) trustee Fairman Rogers.[36] A group of Philadelphians, including Penn Provost William Pepper and the publisher J.B. Lippincott recruited Muybridge to work at Penn under their sponsorship.[36] In 1884, Eakins worked briefly aslope Muybridge in the latter'due south photographic studio at the northeast corner of 36th and Pino streets in Philadelphia.[36] [37]

Eakins shortly performed his ain contained motion studies, also usually involving the nude effigy, and even adult his own technique for capturing movement on moving picture.[38] Whereas Muybridge'south system relied on a series of cameras triggered to produce a sequence of individual photographs, Eakins preferred to use a single camera to produce a series of exposures superimposed on one negative.[39] Eakins was more than interested in precision measurements on a unmarried image to aid in translating a motility into a painting, while Muybridge preferred separate images that could besides be displayed by his primitive pic projector.[37]

After Eakins obtained a camera in 1880, several paintings, such as Mending the Internet (1881) and Arcadia (1883), are known to have been derived at least in function from his photographs. Some figures appear to exist detailed transcriptions and tracings from the photographs by some device like a magic lantern, which Eakins and so took pains to comprehend up with oil paint. Eakins' methods appear to be meticulously applied, and rather than shortcuts, were likely used in a quest for accuracy and realism.[40]

An excellent example of Eakins' use of this new technology is his painting A May Forenoon in the Park, which relied heavily on photographic motion studies to draw the truthful gait of the 4 horses pulling the coach of patron Fairman Rogers. But in typical fashion, Eakins likewise employed wax figures and oil sketches to become the terminal effect he desired.

The so-called "Naked Series", which began in 1883, were nude photos of students and professional models which were taken to prove real human anatomy from several specific angles, and were oft hung and displayed for study at the school. Later, less regimented poses were taken indoors and out, of men, women, and children, including his wife. The most provocative, and the only ones combining males and females, were nude photos of Eakins and a female person model (run across below). Although witnesses and chaperones were ordinarily on site, and the poses were mostly traditional in nature, the sheer quantity of the photos and Eakins' overt brandish of them may have undermined his continuing at the Academy.[41] In all, about 8 hundred photographs are now attributed to Eakins and his circle, well-nigh of which are figure studies, both clothed and nude, and portraits.[42] No other American artist of his time matched Eakins' interest in photography, nor produced a comparable body of photographic works.[43]

Eakins used photography for his own private ends too. Aside from nude men, and women, he also photographed nude children. While the photographs of the nude adults are more artistically equanimous, the younger children and infants are posed less formally. These photographs, that are "charged with sexual overtones," as Susan Danly and Cheryl Leibold write, are of unidentified children.[44] In the catalog of Eakins' collection at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, photo number 308 is of an African American child reclining on a couch and posed equally Venus. Both Saidiya Hartman and Fred Moten write, respectively, about the photograph, and the child that it arrests.

Portraits [edit]

I volition never have to give up painting, for even now I could paint heads good enough to make a living anywhere in America.[46]

For Eakins, portraiture held little interest as a means of fashionable idealization or even simple verisimilitude. Instead, it provided the opportunity to reveal the character of an individual through the modeling of solid anatomical grade.[47] This meant that, notwithstanding his youthful optimism, Eakins would never be a commercially successful portrait painter, as few paid commissions came his way. Only his total output of some two hundred and fifty portraits is characterized by "an uncompromising search for the unique man existence".[48]

Ofttimes this search for individuality required that the subject be painted in his ain daily working environment. Eakins' Portrait of Professor Benjamin H. Rand (1874) was a prelude to what many consider his most of import work.

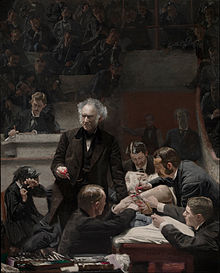

Stunningly illuminated, Dr. Gross is the embodiment of heroic rationalism, a symbol of American intellectual achievement.

-- William Innes Homer[49]

Thomas Eakins: His Life and Art

In The Gross Clinic (1875), a renowned Philadelphia surgeon, Dr. Samuel D. Gross, is seen presiding over an functioning to remove part of a diseased bone from a patient's thigh. Gross lectures in an amphitheater crowded with students at Jefferson Medical College. Eakins spent nearly a year on the painting, again choosing a novel subject, the discipline of modern surgery, in which Philadelphia was in the forefront. He initiated the projection and may take had the goal of a thou work conforming a showing at the Centennial Exposition of 1876.[50] Though rejected for the Art Gallery, the painting was shown on the centennial grounds at an exhibit of a U.Southward. Army Post Hospital. In precipitous dissimilarity, another Eakins submission, The Chess Players, was accepted by the Committee and was much admired at the Centennial Exhibition, and critically praised.[51]

At 96 by 78 inches (240 × 200 cm), The Gross Clinic is 1 of the artist's largest works, and considered by some to be his greatest. Eakins' high expectations at the start of the project were recorded in a letter, "What elates me more is that I take only got a new picture blocked in and it is very far better than anything I take ever done. As I spoil things less and less in finishing I have the greatest hopes of this one"[52] Only if Eakins hoped to impress his abode boondocks with the picture show, he was to exist disappointed; public reaction to the painting of a realistic surgical incision and the resultant claret was ambivalent at best, and it was finally purchased by the college for the unimpressive sum of $200. Eakins borrowed information technology for subsequent exhibitions, where it drew stiff reactions, such as that of the New York Daily Tribune, which both best-selling and damned its powerful image, "but the more than ane praises it, the more one must condemn its admission to a gallery where men and women of weak nerves must be compelled to wait at information technology. For not to await information technology is impossible...No purpose is gained by this morbid exhibition, no lesson taught—the painter shows his skill and the spectators' gorge rises at it—that is all."[53] The higher now describes it thus: "Today the in one case maligned picture is historic as a great nineteenth-century medical history painting, featuring one of the well-nigh superb portraits in American art".[ citation needed ]

In 1876, Eakins completed a portrait of Dr. John Brinton, surgeon of the Philadelphia Infirmary, and famed for his Civil State of war service. Done in a more breezy setting than The Gross Clinic, it was a personal favorite of Eakins, and The Art Journal proclaimed "it is in every respect a more than favorable example of this artist'due south abilities than his much-talked-of composition representing a dissecting room."[54]

Other outstanding examples of his portraits include The Agnew Clinic (1889),[55] Eakins' almost important commission and largest painting, which depicted another eminent American surgeon, Dr. David Hayes Agnew, performing a mastectomy; The Dean's Roll Call (1899), featuring Dr. James W. Kingdom of the netherlands, and Professor Leslie Due west. Miller (1901), portraits of educators standing equally if addressing an audience; a portrait of Frank Hamilton Cushing (c. 1895), in which the prominent ethnologist is seen performing an incantation at the Zuñi pueblo;[56] Professor Henry A. Rowland (1897), a bright scientist whose study of spectroscopy revolutionized his field;[57] Blowsy Music (1900),[58] in which Mrs. William D. Frishmuth is shown seated amongst her collection of musical instruments; and The Concert Singer (1890–92),[59] for which Eakins asked Weda Cook to sing "O balance in the Lord", so that he could study the muscles of her pharynx and mouth. To replicate the proper deployment of a baton, Eakins enlisted an orchestral usher to pose for the hand seen in the lower left-hand corner of the painting.[60]

Of Eakins' later portraits, many took as their subjects women who were friends or students. Unlike nigh portrayals of women at the time, they are devoid of glamor and idealization.[61] For Portrait of Letitia Wilson Jordan (1888), Eakins painted the sitter wearing the aforementioned evening dress in which he had seen her at a party. She is a substantial presence, a vision quite different from the era's fashionable portraiture. So, too, his Portrait of Maud Melt (1895), where the obvious beauty of the field of study is noted with "a stark objectivity".[62]

The portrait of Miss Amelia Van Buren (c. 1890), a friend and former educatee, suggests the melancholy of a complex personality, and has been chosen "the finest of all American portraits".[63] Fifty-fifty Susan Macdowell Eakins, a strong painter and former educatee who married Eakins in 1884,[64] was not sentimentalized: despite its richness of color, The Artist's Wife and His Setter Domestic dog (c. 1884–89) is a penetratingly candid portrait.[65]

Some of his near vivid portraits resulted from a late series done for the Catholic clergy, which included paintings of a cardinal, archbishops, bishops, and monsignors. As usual, most of the sitters were engaged at Eakins' request, and were given the portraits when Eakins had completed them. In portraits of His Eminence Sebastiano Cardinal Martinelli (1902), Archbishop William Henry Elderberry (1903), and Monsignor James P. Turner (c. 1906), Eakins took advantage of the brilliant vestments of the offices to animate the compositions in a way not possible in his other male portraits.

Securely affected past his dismissal from the Academy, Eakins focused his after career on portraiture, such equally his 1905 Portrait of Professor William South. Forbes. His steadfast insistence on his own vision of realism, in addition to his notoriety from his schoolhouse scandals, combined to hurt his income in later years. Even as he approached these portraits with the skill of a highly trained anatomist, what is nigh noteworthy is the intense psychological presence of his sitters. Withal, it was precisely for this reason that his portraits were ofttimes rejected past the sitters or their families.[66] As a result, Eakins came to rely on his friends and family members to model for portraits. His portrait of Walt Whitman (1887–1888) was the poet'south favorite.[67]

The figure [edit]

Eakins' lifelong interest in the figure, nude or near so, took several thematic forms. The rowing paintings of the early 1870s institute the showtime series of figure studies. In Eakins' largest picture on the field of study, The Biglin Brothers Turning the Stake (1873), the muscular dynamism of the body is given its fullest treatment.

In the 1877 painting William Rush and His Model, he painted the female person nude every bit integral to a historical subject area, fifty-fifty though at that place is no evidence that the model who posed for Rush did so in the nude. The Centennial Exhibition of 1876 helped foster a revival in interest in Colonial America and Eakins participated with an ambitious projection employing oil studies, wax and woods models, and finally the portrait in 1877. William Blitz was a celebrated Colonial sculptor and ship carver, a revered instance of an creative person-citizen who figured prominently in Philadelphia civic life, and a founder of the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts where Eakins had started educational activity.

Despite his sincerely depicted reverence for Rush, Eakins' treatment of the human body one time once more drew criticism. This time it was the nude model and her heaped-upwardly clothes depicted forepart and center, with Blitz relegated to the deep shadows in the left groundwork, that stirred dissatisfaction. Nevertheless, Eakins found a subject that referenced his native urban center and an earlier Philadelphia creative person, and allowed for an assay on the female person nude seen from behind.[68]

When he returned to the subject many years afterwards, the narrative became more personal: In William Rush and His Model (1908), gone are the chaperon and detailed interior of the earlier work. The professional distance between sculptor and model has been eliminated, and the relationship has become intimate. In one version of the painting from that year, the nude is seen from the front, being helped down from the model stand by an artist who bears a strong resemblance to Eakins.[69]

The Swimming Hole (1884–85) features Eakins' finest studies of the nude, in his almost successfully constructed outdoor picture show.[lxx] The figures are those of his friends and students, and include a cocky-portrait. Although at that place are photographs by Eakins which chronicle to the painting, the movie's powerful pyramidal composition and sculptural conception of the individual bodies are completely distinctive pictorial resolutions.[71] The work was painted on commission, but was refused.[72]

In the late 1890s Eakins returned to the male person figure, this fourth dimension in a more urban setting. Taking the Count (1896), a painting of a prizefight, was his second largest canvas, simply not his well-nigh successful limerick.[73] The same may be said of Wrestlers (1899). More successful was Between Rounds (1899), for which boxer Billy Smith posed seated in his corner at Philadelphia'southward Loonshit; in fact, all the chief figures were posed past models re-enacting what had been an actual fight.[74] Salutat (1898), a frieze-like limerick in which the principal figure is isolated, "is ane of Eakins' finest achievements in effigy-painting."[75]

Although Eakins was agnostic, he painted The Crucifixion in 1880.[76] Art historian Akela Reason says

Eakins's selection of this subject has puzzled some art historians who, unable to reconcile what appears to exist an dissonant religious image by a reputedly agnostic artist, have related it solely to Eakins's desire for realism, thus divesting the painting of its religious content. Lloyd Goodrich, for instance, considered this illustration of Christ's suffering completely devoid of "religious sentiment" and suggested that Eakins intended it simply as a realist study of the male nude body. As a outcome, art historians accept oft associated 'Crucifixion' (like Swimming) with Eakins'due south potent interest in anatomy and the nude.[77]

In his subsequently years Eakins persistently asked his female portrait models to pose in the nude, a practice which would have been all but prohibited in conventional Philadelphia society. Inevitably, his desires were frustrated.[78]

Personal life and spousal relationship [edit]

The nature of Eakins' sexuality and its impact on his fine art is a matter of intense scholarly debate. Stiff circumstantial evidence points to discussion during Eakins'southward lifetime that he had homosexual leanings, and there is footling doubt that he was attracted to men,[79] as evidenced in his photography, and three major paintings where male person buttocks are a focal point: The Gross Dispensary, Salutat, and The Swimming Hole. The latter, in which Eakins appears, is increasingly seen as sensuous and autobiographical.[80]

Until recently, major Eakins scholars persistently denied he was homosexual, and such discussion was marginalized. While there is nonetheless no consensus, today give-and-take of homoerotic desire plays a large part in Eakins scholarship.[81] The discovery of a big trove of Eakins' personal papers in 1984 has also driven reassessment of his life.[82]

Eakins met Emily Sartain, daughter of John Sartain, while studying at the academy. Their romance foundered subsequently Eakins moved to Paris to report, and she defendant him of immorality. It is probable Eakins had told her of frequenting places where prostitutes assembled. The son of Eakins' physician also reported that Eakins had been "very loose sexually—went to French republic, where in that location are no morals, and the french morality suited him to a T".[83]

In 1884, at historic period twoscore, Eakins married Susan Hannah Macdowell, the daughter of a Philadelphia engraver. Two years earlier Eakins' sister Margaret, who had acted every bit his secretary and personal servant, had died of typhoid. It has been suggested that Eakins married to supercede her.[84] Macdowell was 25 when Eakins met her at the Hazeltine Gallery where The Gross Clinic was being exhibited in 1875. Dissimilar many, she was impressed past the controversial painting and she decided to written report with him at the University, which she attended for six years, adopting a sober, realistic manner similar to her teacher's. Macdowell was an outstanding pupil and winner of the Mary Smith Prize for the all-time painting past a matriculating woman artist.[85] [86]

During their childless spousal relationship, she painted only sporadically and spent almost of her time supporting her hubby's career, entertaining guests and students, and faithfully backing him in his hard times with the academy, even when some members of her family aligned against Eakins.[87] She and Eakins both shared a passion for photography, both every bit photographers and subjects, and employed it as a tool for their fine art. She likewise posed nude for many of his photos and took images of him. Both had carve up studios in their home. Afterwards Eakins' death in 1916, she returned to painting, adding considerably to her output right up to the 1930s, in a style that became warmer, looser, and brighter in tone. She died in 1938. Thirty-five years afterwards her decease, in 1973, she had her starting time 1-woman exhibition at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.[85]

In the latter years of his life, Eakins' constant companion was the handsome sculptor Samuel Murray, who shared his interest in boxing and bicycling. The evidence suggests the relationship was more than emotionally important to Eakins than that with his wife.[88]

Throughout his life, Eakins appears to take been fatigued to those who were mentally vulnerable then preyed upon those weaknesses. Several of his students ended their lives in insanity.[89]

Death and legacy [edit]

Eakins died on June 25, 1916, at the age of 71 and is buried at The Woodlands, which is located well-nigh the University of Pennsylvania in Westward Philadelphia.[ninety]

Late in life Eakins did experience some recognition. In 1902 he was made a National Academician. In 1914 the sale of a portrait study of D. Hayes Agnew for The Agnew Dispensary to Dr. Albert C. Barnes precipitated much publicity when rumors circulated that the selling price was fifty thousand dollars. In fact, Barnes bought the painting for four thousand dollars.[91]

In the yr after his expiry, Eakins was honored with a memorial retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and in 1917–eighteen the Pennsylvania Academy followed accommodate. Susan Macdowell Eakins did much to preserve his reputation, including giving the Philadelphia Museum of Art more than fifty of her married man's oil paintings.[92] Afterwards her death in 1938, other works were sold off, and eventually another large collection of fine art and personal material was purchased by Joseph Hirshhorn, and now is part of the Hirshhorn Museum's collection.[93] Since then, Eakins' domicile in North Philadelphia was put on the National Register of Celebrated Places list in 1966, and Eakins Oval, beyond from the Philadelphia Museum of Art on the Benjamin Franklin Parkway, was named for the artist.[94] [95] In 1967 The Biglin Brothers Racing (1872) was reproduced on a United States stamp. His piece of work was also office of the painting issue in the art contest at the 1932 Summer Olympics.[96]

Eakins' attitude toward realism in painting, and his desire to explore the heart of American life proved influential. He taught hundreds of students, amid them his future wife Susan Macdowell, African-American painter Henry Ossawa Tanner, and Thomas Anshutz, who taught, in plow, Robert Henri, George Luks, John Sloan, and Everett Shinn, time to come members of the Ashcan School, and other realists and creative heirs to Eakins' philosophy.[97] Though his is not a household name, and though during his lifetime Eakins struggled to brand a living from his work, today he is regarded as i of the about of import American artists of any menses.

Thomas Eakins Carrying a Woman, 1885. Photograph, circle of Eakins.

Since the 1990s, Eakins has emerged as a major figure in sexuality studies in art history, for both the homoeroticism of his male nudes and for the complication of his attitudes toward women. Controversy shaped much of his career as a teacher and equally an artist. He insisted on instruction men and women "the aforementioned", used nude male person models in female classes and vice versa, and was accused of abusing female students.[98]

Recent scholarship suggests that these scandals were grounded in more than the "puritanical prudery" of his contemporaries—as had once been assumed—and that Eakins' progressive academic principles may have protected unconscious and dubious agendas.[99] These controversies may have been caused past a combination of factors such as the bohemianism of Eakins and his circle (in which students, for example, sometimes modeled in the nude for each other), the intensity and authorization of his educational activity style, and Eakins' inclination toward unorthodox or provocative behavior.[100] [101]

Disposition of estate [edit]

Eakins was unable to sell many of his works during his lifetime, and then when he died in 1916, a big body of artwork passed to his widow, Susan Macdowell Eakins. She advisedly preserved information technology, donating some of the strongest pieces to various museums. When she in plough died in 1938, much of the remaining artistic estate was destroyed or damaged by executors, and the remainders were late salvaged by a erstwhile Eakins educatee. For more than details, come across the commodity "Listing of works past Thomas Eakins".

On November eleven, 2006, the Board of Trustees at Thomas Jefferson Academy agreed to sell The Gross Dispensary to the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, and the Crystal Bridges Museum of American Art in Bentonville, Arkansas for a record $68,000,000, the highest price for an Eakins painting equally well as a record price for an individual American-made portrait.[102] On December 21, 2006, a group of donors agreed to match the price to keep the painting in Philadelphia. It is displayed alternately at the Philadelphia Museum of Art and at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts.

Assessment [edit]

On October 29, 1917, Robert Henri wrote an open letter to the Art Students League well-nigh Eakins:

Thomas Eakins was a human being of great character. He was a man of iron will and his will to paint and to carry out his life as he thought information technology should go. This he did. It price him heavily but in his works nosotros have the precious consequence of his independence, his generous eye and his big mind. Eakins was a deep student of life, and with a great dear he studied humanity bluntly. He was not afraid of what his study revealed to him. In the matter of ways and means of expression, the science of technique, he studied most profoundly, as only a smashing master would have the will to written report. His vision was non touched past manner. He struggled to apprehend the constructive strength in nature and to employ in his works the principles institute. His quality was honesty. "Integrity" is the word which seems best to fit him. Personally I consider him the greatest portrait painter America has produced.[103]

In 1982, in his two-volume Eakins biography, art historian Lloyd Goodrich wrote:

In spite of limitations—and what creative person is free of them?—Eakins' accomplishment was monumental. He was our get-go major painter to have completely the realities of contemporary urban America, and from them to create powerful, profound fine art... In portraiture alone Eakins was the strongest American painter since Copley, with equal substance and ability, and added penetration, depth, and subtlety.[104]

John Canaday, art critic for The New York Times, wrote in 1964:

Equally a supreme realist, Eakins appeared heavy and vulgar to a public that idea of art, and culture in general, largely in terms of a graceful sentimentality. Today he seems to us to have recorded his young man Americans with a perception that was often as tender as it was vigorous, and to take preserved for us the essence of an American life which, indeed, he did not idealize—considering it seemed to him beautiful across the necessity of idealization.[105]

In 2010, the American painter Philip Pearlstein published an article in ARTnews suggesting the strong influences Eadweard Muybridge'southward piece of work and public lectures had on 20th-century artists, including Degas, Rodin, Seurat, Duchamp, and Eakins, either direct or through the contemporaneous work of their young man photographic pioneer, Étienne-Jules Marey.[106] He concluded:

I believe that both Muybridge and Eakins—as a photographer—should be recognized every bit amidst the near influential artists on the ideas of 20th-century art, forth with Cézanne, whose lessons in fractured vision provided the technical basis for putting those ideas together.[106]

Run across likewise [edit]

- List of painters by name beginning with "E"

- List of American artists before 1900

- List of people from Philadelphia

- Visual fine art of the U.s.a.

Notes [edit]

- ^ "Thomas Eakins: Photography, 1880s–1890s". Heilbrunn timeline of art history. Metropolitan Art Museum in New York. Retrieved Dec 21, 2015.

- ^ TFAOI.com, Philadelphia Museum of Art. Retrieved July 27, 2009

- ^ Whitman, -Walt (December 3, 2001). "Thomas Eakins | PBS". American Masters.

- ^ Goodrich, Volume II, p. 285.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. I, pp. ane–iv.

- ^ Amy B. Werbel, Thomas Eakins, Philadelphia Museum of Fine art, 2001, ISBN 0-87633-142-8, p. 5

- ^ "Charles Lewis Fussell (1840–1909)" (PDF). schwarzgallery.com. 2007. Retrieved January 16, 2018.

- ^ Amy B. Werbel, p. 10

- ^ Canaday, John: "Thomas Eakins; Familiar truths in clear and cute language", Horizon, p. 96. Vol. VI, no. 4, Autumn, 1964.

- ^ H. Barbara Weinberg, Thomas Eakins, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001, ISBN 0-87633-142-8, p. 15

- ^ Homer, William Innes, Thomas Eakins: His Life and Art, p. 36. Abbeville Press, 1992.

- ^ Updike, John: "The Ache in Eakins", Still Looking, p. 80. Alfred A. Knopf, 2005.

- ^ In a big film you can encounter what o'clock it is afternoon or morning if it'due south hot or cold winter or summer and what kind of people are there and what they are doing and why they are doing it. Homer, p. 36.

- ^ Spanish work [is] so adept so potent so reasonable and then free from every affectation. Information technology stands out like nature itself... Updike, p. 72.

- ^ Homer, p. 44.

- ^ H. Barbara Weinberg, p. 23

- ^ Marc Simpson, Thomas Eakins, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001, ISBN 0-87633-142-viii, p. 28

- ^ Perspective drawings for another rowing painting, The Pair-Oared Shell, were then precise that one researcher claimed not merely to be able to reconstruct distances within the movie, simply to establish the position of the sun so as to ascertain the scene'due south dating as vii:20 P.M. on either May 28 or July 27. Cited in Sewell, p. 17.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. I, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Marc Simpson, p. 29

- ^ "These works have their own kind of sober poetry." Goodrich, Vol. I, p. 71.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. I, p. 81.

- ^ Kathleen A. Foster, Thomas Eakins, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001, ISBN 0-87633-142-viii, p. 102

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. I, p. 282.

- ^ Sewell, p. 78.

- ^ Weinberg, H. Barbara, Thomas Eakins and the Metropolitan Museum of Art, p. 28. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1994.

- ^ Kathleen A. Foster, p. 102

- ^ Eakins, letter of the alphabet to Edward Hornor Coates, September 11, 1886, cited in Homer, p. 166.

- ^ Eakins, letter to Edward Hornor Coates, September 12, 1886, cited in Homer, p. 166.

- ^ Homer, p. 173.

- ^ Kathleen A. Foster, p. 105

- ^ "For a similar gesture he lost his position at the Drexel plant in 1895, after a number of female sitters complained of what would at present be called sexual harassment." Updike, p. 80.

- ^ Kathleen A. Foster (ed.), A Drawing Manual by Thomas Eakins, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2005 (ISBN 0-87633-176-ii)

- ^ Rosenheim, Jeff 50., "Thomas Eakins, Creative person-Photographer, in the Metropolitan Museum of Art", Thomas Eakins and the Metropolitan Museum, p. 45. The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, 1994.

- ^ "By 1879 Eakins was in direct communication with Muybridge." Goodrich, Vol. I, p. 263.

- ^ a b c Brockmeier, Erica K. (February 17, 2020). "A new way of thinking virtually motion, motion, and the concept of time". Penn Today . Retrieved March 14, 2022.

- ^ a b Brookman, Philip; Marta Braun; Andy Grundberg; Corey Keller; Rebecca Solnit (2010). Helios : Eadweard Muybridge in a time of modify. [Göttingen, Frg]: Steidl. p. 93. ISBN9783865219268.

- ^ "With their sequential merely overlapping forms, Eakins'southward motion studies created a truer depiction of kinetics than the contemporaneous pictures made on separate plates in separate cameras by Eadweard Muybridge, his colleague at the University of Pennsylvania." Rosenheim, p. l.

- ^ Sewell, p. 82.

- ^ Tucker and Gutman, Thomas Eakins, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001, ISBN 0-87633-142-8, pp. 229, 238

- ^ W. Douglass Paschall, Thomas Eakins, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2001, ISBN 0-87633-142-viii, pp. 251, 238

- ^ Rosenheim, p. 45.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. I, p. 260.

- ^ Danly, Susan., and Cheryl. Leibold. Eakins and the Photograph: Works by Thomas Eakins and His Circle in the Collection of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. Washington: Published for the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts by the Smithsonian Institution Printing, 1994. p. 184

- ^ Cited in Sewell, p. 43.

- ^ Eakins in a letter of the alphabet home to his father, June 1869. Goodrich, Vol. I, p. fifty.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. 2, pp. 57–58.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. II, pp. 58–59.

- ^ Homer, p. 75.

- ^ Marc Simpson, p. 32

- ^ Marc Simpson, pp. 33–34

- ^ Eakins to Earl Shinn, in a letter of the alphabet dated April xiii, 1875, Richard Tapper Cadbury Collection, Friends Historical Library, Swarthmore Higher, Swarthmore, Pennsylvania.

- ^ Marc Simpson, p. 33

- ^ Marc Simpson, p. 35

- ^ The Agnew Clinic. Swarthmore College Archived Apr xx, 2007, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 26 March 2007.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. II, p. 132.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. II, p. 137.

- ^ Antiquated Music, Philadelphia Museum of Art Retrieved on 26 March 2007.

- ^ The Concert Singer. Swarthmore Higher Archived April 20, 2007, at the Wayback Motorcar Retrieved on 26 March 2007.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. Ii, p. 84.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. 2, p. 67.

- ^ Homer, p. 224.

- ^ Canaday, p. 95.

- ^ Portrait of Thomas Eakins. Philadelphia Museum of Fine art. Philamuseum.org Retrieved on 26 March 2007.

- ^ The Artist's Wife and His Setter Dog. Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, Timeline of Art History. Metmuseum.org Retrieved on 26 March 2007.

- ^ When asked why he did not sit for a portrait past Eakins, the creative person Edwin Austin Abbey said: "For the reason that he would bring out all those traits of my character I have been trying to conceal from the public for years." Goodrich, Vol. II, p. 77.

- ^ Whitman famously wrote Eakins is not a painter, he is a force. Goodrich, Vol. II, p. 35.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. I, p. 147.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. Ii, p. 247.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. I, p. 240.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. I, pp. 239–41.

- ^ Edward Hornor Coates deputed the painting. It was Coates who, as chairman of the Committee on Education at the Pennsylvania Academy, was soon to request Eakins' resignation. Goodrich, Vol. I, p. 286.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. II, p. 147.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. 2, p. 149.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. II, pp. 151–52.

- ^ Amy Beth Werbel (2007). Thomas Eakins: Art, Medicine, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia. Yale University Press. p. 37. ISBN9780300116557.

Given Eakins' outspoken agnosticism, his motivation to pigment a crucifixion scene is frankly curious.

- ^ Akela Reason (2010). Thomas Eakins and the Uses of History. Academy of Pennsylvania Printing. p. 119. ISBN9780812241983.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. II, pp. 91–95.

- ^ McFeely, William S. Portrait: The Life Of Thomas Eakins, W. W. Norton & Visitor, 2007, ISBN 0393330680, pp. 47, 51, 128

- ^ Adams 2005, pp. 115–17, 306. sfn mistake: no target: CITEREFAdams2005 (aid)

- ^ Adams, Henry Eakins Revealed: The Secret Life of an American Artist, Oxford University Printing, pp. 46, 309–x, 444

- ^ Adams 2005, p. 42. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAdams2005 (aid)

- ^ Adams 2005, p. 90. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAdams2005 (assist)

- ^ Adams 2005, p. twoscore. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAdams2005 (help)

- ^ a b Askart.com. Retrieved 7 December 2007.

- ^ Gaze, Delia (1997). Dictionary of Women Artists: Artists, J–Z. Taylor & Francis. ISBN978-1-884964-21-iii.

- ^ Solomon, Deborah (April 2, 2006). "A Life in Somber Tones". The New York Times . Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ Adams 2005, p. 444. sfn error: no target: CITEREFAdams2005 (help)

- ^ Adams 2005, p. 445. sfn fault: no target: CITEREFAdams2005 (assist)

- ^ Wilson, Scott. Resting Places: The Burying Sites of More Than xiv,000 Famous Persons, 3d ed.: 2 (Kindle Location 13520). McFarland & Visitor, Inc., Publishers. Kindle Edition.

- ^ Homer, p. 249.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. II, p. 282.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. Two, p. 284.

- ^ "Pennsylvania – Philadelphia Canton". National Register of Celebrated Places.com. Retrieved April xx, 2007.

- ^ "Eakins Oval". Abode&Abroad. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. Retrieved April 20, 2007.

- ^ "Thomas Eakins". Olympedia . Retrieved August iv, 2020.

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. Two, p. 309.

- ^ Kirkpatrick, Sidney. The Revenge of Thomas Eakins p. 311, Yale Academy Press, 2006. ISBN 0-300-10855-9, ISBN 978-0-300-10855-2

- ^ Sewell et al. 2001, pp. 104

- ^ Sewell et al. 2001, pp. 104–05

- ^ Homer, pp. 173–82

- ^ Shattuck, Kathryn. Got Medicare? A ,eight One thousand thousand Operation. The New York Times, November 19, 2006. NYtimes.com Retrieved on 31 March 2007.

- ^ Thomas Eakins Spartacus-Educational.com Archived 25 October 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved December 15, 2007

- ^ Goodrich, Vol. II, p. 289.

- ^ Canaday, p. 89.

- ^ a b Pearlstein, Philip (December ane, 2010). "Moving Targets". ARTnews.com . Retrieved March 15, 2022.

Farther reading [edit]

- Adams, Henry: Eakins Revealed: The Hole-and-corner Life of an American Artist. Oxford University Press, 2005. ISBN 0-xix-515668-4.

- Berger, Martin: Homo Fabricated: Thomas Eakins and the Structure of Golden Age Manhood. University of California Press, 2000. ISBN 0-520-22209-1.

- Brown, Dotty: Boathouse Row: Waves of Change in the Birthplace of American Rowing. Temple University Press, 2017. ISBN 9781439912829.

- Canaday, John: Thomas Eakins; "Familiar truths in clear and beautiful language", Horizon. Volume Vi, Number 4, Fall 1964.

- Dacey, Philip: The Mystery of Max Schmitt, Poems on the Life of Thomas Eakins". Turning Betoken Press, 2004. ISBN 1932339469

- Doyle, Jennifer: "Sexual practice, Scandal, and 'The Gross Clinic'". Representations 68 (Fall 1999): 1–33.

- Goodrich, Lloyd (1933). Thomas Eakins . New York: Whitney Museum of American Art.

- Goodrich, Lloyd: Thomas Eakins. Harvard Academy Press, 1982. ISBN 0-674-88490-6

- Homer, William Innes: Thomas Eakins: His Life and Fine art. Abbeville Press, 1992. ISBN 1-55859-281-4

- Johns, Elizabeth: Thomas Eakins. Princeton University Press, 1991. ISBN 0-691-00288-vi

- Kirkpatrick, Sidney: The Revenge of Thomas Eakins. Yale University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-300-10855-nine.

- Lubin, David: Acts of Portrayal: Eakins, Sargeant, James. Yale Academy Press, 1985. ISBN 0-300-03213-7

- Sewell, Darrel; et al. Thomas Eakins. Yale Academy Press, 2001. ISBN 0-87633-143-6

- Sewell, Darrel: Thomas Eakins: Creative person of Philadelphia. Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1982. ISBN 0-87633-047-2

- Sullivan, Mark W. "Thomas Eakins and His Portrait of Begetter Fedigan," Records of the American Catholic Historical Society of Philadelphia, Vol. 109, No. 3-four (Fall-Winter 1998), pp. 1–23.

- Updike, John: Still Looking: Essays on American Art. Alfred A. Knopf, 2005. ISBN 1-4000-4418-9

- Weinberg, H. Barbara: Thomas Eakins and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Fine art, 1994. Publication no: 885-660

- Werbel, Amy: Thomas Eakins: Art, Medicine, and Sexuality in Nineteenth-Century Philadelphia. Yale University Printing, 2007. ISBN 978-0-300-11655-vii.

- The Paris Messages of Thomas Eakins. Edited past William Innes Homer. Princeton, Princeton Academy Printing, 2009, ISBN 978-0-691-13808-4

- Braddock, Alan: Thomas Eakins and The Cultures of Modernity. University of California Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-520-25520-3

- Weinberg, H Barbara (2009). American impressionism and realism . New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (run across index)

External links [edit]

- Thomaseakins.org, 148 works by Thomas Eakins

- Thomas Eakins Exhibition at The Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Thomas Eakins messages online at the Smithsonian Archives of American Art

- Selections from the Seymour Adelman collection, 1845–1958 features a collection of documents relating to Eakins and his family unit from the Athenaeum of American Fine art

- Works by Thomas Eakins at Bryn Mawr Higher

- "Introduction". Thomas Eakins: Scenes from modern life. WHYY, Incorporated. 2002. Retrieved May 23, 2012. Documentary movie broadcast on PBS network in 2002

- Thomas Eakins at Find a Grave

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thomas_Eakins

0 Response to "Sartain William Thomas Eakins the Art World 3 No 4 1918 29193"

Post a Comment